Fetal Homicide: Recognizing the Youngest Victims of Crime

Margaret Somerville, director of the Centre for Medicine, Ethics and Law at

Margaret Somerville, director of the Centre for Medicine, Ethics and Law at **********

Recognizing the Youngest Victims of Crime

In the past three years, in

A Environics poll asking if killing or injuring a foetus should be a crime found that 75 per cent of Canadian women and 68 per cent of men would support a foetal protection law (the level of support among all Canadians was 72 per cent). The same poll found that, overall, 62 per cent of Canadians supported legal protection of the unborn child at some point before or at viability. (The Canadian Medical Association guidelines define foetal viability -- the possibility that the foetus can survive outside its mother’s womb -- to be 20 weeks gestation and/or 500 grams in weight.)

In short, many Canadians’ moral intuition is that "there ought to be a law" or laws protecting foetuses from some harms, although we don’t all agree on what those laws should be, especially in the context of abortion. Presently in

The Supreme Court of Canada has consistently ruled that under our current law the foetus does not exist as a protectable human being, and the Criminal Code legislates that a child becomes a human being for the purposes of a homicide offence only after it is born alive. This means that criminal liability specifically for the wrong of killing the foetus in the course of a criminal act cannot at present be imposed. Only the wrong to the mother is legally cognisable.

Proposals for an Unborn Victims of Crime Act are adamantly opposed by pro-choice abortion advocates, for fear that any legal recognition of the foetus will lead to the re-criminalisation of abortion. They accuse pro-life supporters of promoting such legislation as a backdoor way to prohibit abortion. It’s true that it could cause us to view the foetus and, therefore, abortion differently. But wilful blindness on our part as a society is not an ethical approach to dealing with abortion.

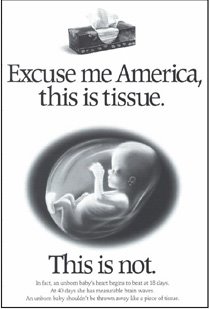

Seeing the foetus as an unborn victim of crime strips away the medical cloak that abortion places on the taking of its life, a cloak that dulls our moral intuitions as to what is involved. It causes us to see the foetus as what it is, an early human life. Those who support abortion must be able to square that fact with their belief that abortion is ethical in all or certain circumstances. Simply arguing for a woman’s right to choose and having no legal prohibitions on abortion does not make it so.

Paradoxically, in one sense, an "unborn victims of violence" law is consistent with a pro-choice stance: it is the other side of the choice coin. It would recognise that women have the "right to choose to bring their child to term in safety", the "right to choose life for their child". Killing or injuring the foetus without the woman’s consent, whether or not there was violence to her, would be an offence.

Pro-choice advocates who don't support this legislation are being inconsistent. If they really are pro-choice they should respect and promote any and all choices for the woman, not just the one to abort. To do otherwise, is not pro-choice, but pro-abortion.

Abortion is always a moral and ethical issue -- or it should always be. The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Reverend Rowan Williams, writing recently, in London, England’s The Observer, says however that we have lost our sense that abortion involves a "major moral choice" – it’s been "normalised" – "something has happened to our assumptions about the life of the unborn child, …when one third of pregnancies in Europe end in abortion".

That abortion is a moral and ethical issue does not mean, however, that it should always be a legal issue. But neither should it never be a legal issue.

As the legal void highlighted by the tragic murders of pregnant women show, we need to re-think our overall approach with respect to the law relating to pre-birth human life, including in the context of abortion. And we should do this within a context that includes women’s informed consent and the recognition of foetal pain.

Informed consent law requires that a woman must be given certain information if her consent to abortion is to be legally valid, in particular, information about the mental and physical health risks to her of abortion. These risks continue to be identified.

Whether the information should extend to a description of prenatal development, including ultrasound or other images of the foetus, abortion alternatives, and so on, before a physician may perform an abortion, is controversial.

A "Foetal Pain Awareness Act", similar to those some American states have enacted, could require a physician inform the woman before an abortion that scientific evidence suggests that after 20 weeks gestation the foetus can feel pain. Furthermore, she would have to be offered anaesthesia for the foetus, which it would be her choice to take or decline. This type of law does not prohibit abortion; rather its goal is to try to prevent the foetus from dying in excruciating pain. After all, even jurisdictions that allow capital punishment prohibit certain forms of it on the grounds they constitute cruel punishment, and we have criminal laws that protect animals from brutal treatment.

The foetus is new human life. That matters ethically and should matter legally. An Unborn Victims of Crime law would recognise that. What law should govern abortion is a separate, but important, issue that raises some different considerations, but having no law is not a neutral stance. It contravenes values that form part of the bedrock of Canadian society.

Margaret Somerville is director of the Centre for Medicine, Ethics and Law at

[Source]

Labels: abortion commentary, fetal homicide

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home